The Dissenter

Socialist  , https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/positions/#4 | Rosa Luxemburg on the fringes of the International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart, 1907. economist

, https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/positions/#4 | Rosa Luxemburg on the fringes of the International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart, 1907. economist  , https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#3 | With a PhD in economics, Rosa Luxemburg taught economic history at the SPD party school from 1908 to 1914. independent woman

, https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#3 | With a PhD in economics, Rosa Luxemburg taught economic history at the SPD party school from 1908 to 1914. independent woman  , https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#3 | Elected in Amsterdam in 1904, the International Socialist Bureau (ISB), which was mostly made up of old men and to which Rosa Luxemburg belonged until 1914. poetic correspondent

, https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#3 | Elected in Amsterdam in 1904, the International Socialist Bureau (ISB), which was mostly made up of old men and to which Rosa Luxemburg belonged until 1914. poetic correspondent  https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/category/material/letters | Facsimile of a letter Rosa Luxemburg wrote to Luise Kautsky while imprisoned at Wronke Fortress (near Posen, now Poznan). and passionate lover of nature

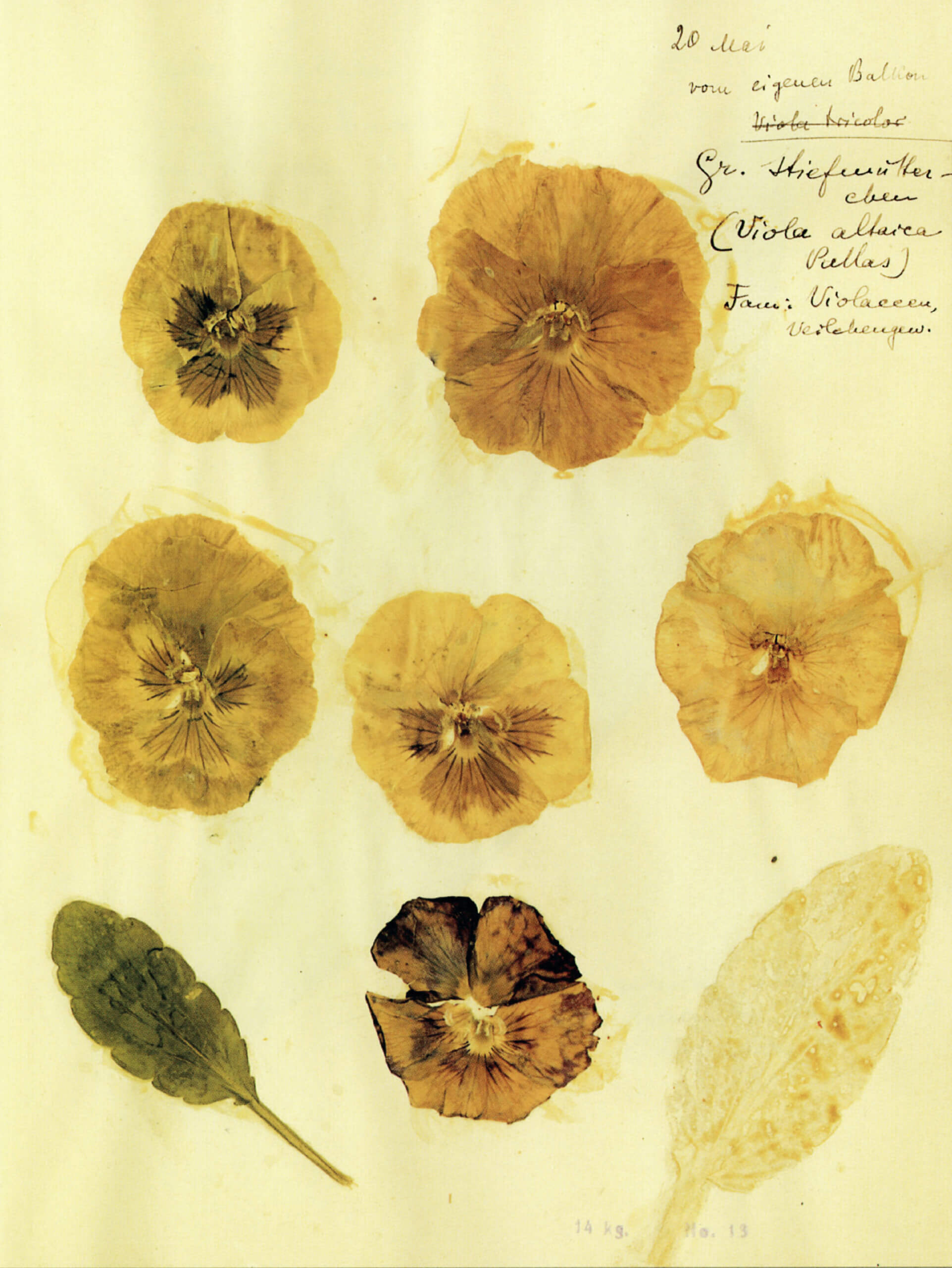

https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/category/material/letters | Facsimile of a letter Rosa Luxemburg wrote to Luise Kautsky while imprisoned at Wronke Fortress (near Posen, now Poznan). and passionate lover of nature  https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#9| Excerpts from the herbarium that Rosa Luxemburg continued to fill with material, even while in prison.. Rosa Luxemburg was many things—and even more was projected onto her

https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#9| Excerpts from the herbarium that Rosa Luxemburg continued to fill with material, even while in prison.. Rosa Luxemburg was many things—and even more was projected onto her  https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#10 | Memorial to Rosa Luxemburg by the Landwehrkanal, in which her body was sunk on 15 January 1919. after she was murdered. The 5th of March 2021

https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#10 | Memorial to Rosa Luxemburg by the Landwehrkanal, in which her body was sunk on 15 January 1919. after she was murdered. The 5th of March 2021  https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#1 | Rosa Luxemburg at age twelve. is the 150th anniversary of her birth.

https://www.rosaluxemburg.org/en/decisions/#1 | Rosa Luxemburg at age twelve. is the 150th anniversary of her birth.

“To say what is remains the most revolutionary act.”[1]

What can we learn from the life and work of Rosa Luxemburg? How would she describe the present crisis of capitalism? Given growing social inequality and the climate crisis, would she call for a mass strike? Would Luxemburg, who during her life wished to have nothing to do with feminism, now describe herself as a feminist?

What do we know about her life? In summer, holidays—and otherwise the desk, printing presses, speeches in beer halls and on horse-pulled carts. Stormy love affairs—and: one more article, the next address, yet another election speech, copious reading every day, but seldom time for a book of her own. And amid all that, prison time, whether for lèse-majesté, a revolution, or exhortations to disobedience. Which decisions led to her becoming a socialist revolutionary?

Luxemburg’s political positions emerged in the same way as she felt forced to live: “unsystematically”. We have been able to excavate them but slowly, and often to our surprise. Many of them remain unknown to this day.Finally, the collection of materials here presents letters, articles, videos, and audio recordings by and about Rosa Luxemburg.

“I enjoy life most in the midst of the storm.”«[2]

With this website, the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung introduces the woman to whose legacy it is committed. The current pandemic has necessitated alterations to our plans, but we will still do as we have promised: celebrate Rosa Luxemburg’s 150th anniversary! The programme includes, among other things, an international conference on 4 and 5 March 2021 on the global reception of Luxemburg’s life and work, an online stream with lectures, interviews and artistic contributions, and a collaboration with the Berliner Volksbühne on their web series Rosa Kollektiv: Oder aktiviere dein inneres Proletariat! (Rosa Collective: Or, Activate Your Inner Proletariat!).

Fußnoten

- Rosa Luxemburg, “In revolutionärer Stunde: Was weiter?” in Gesammelte Werke, vol. 2, Berlin, 1972, p. 36.

- Rosa Luxemburg, letter to Mathilde and Robert Siedel, 20 May 1910, Gesammelte Briefe, vol. 3, Berlin 1982, p. 160. English translation in The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg, edited by Georg Adler, Peter Hudis, and Annelies Laschitza, London, 2011.